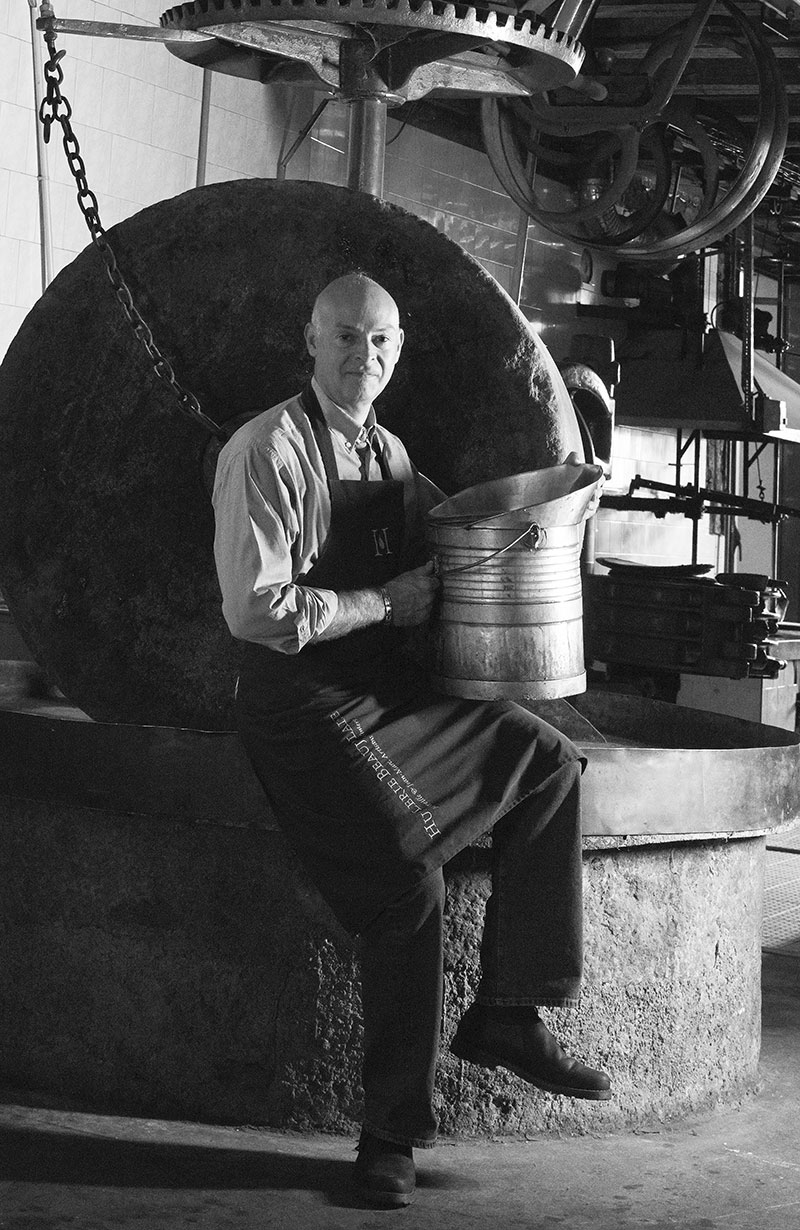

From an early age, he showed an innate talent for tinkering and understanding the workings of the world around him. This taste for technical challenges and his intimate connection with nature led him to take up a daring challenge: to breathe new life into an abandoned oil mill at the back of his parents' hardware store, transforming ruins into a veritable sanctuary of taste.

“I wanted to learn to feel the weather, understand the soul of the fruit and offer an oil that was true to its essence,” he explains. Jean-Marc didn't inherit an oil-making tradition: he built it with his own hands, tireless energy and a clear vision. The restoration of the mill marks the beginning of an extraordinary human and artisanal adventure.

His demand for quality and his love of a job well done soon led him to collaborate with some of the greatest names in French gastronomy, including Régis Marcon, Michel Troisgros and many others. Together, they have imagined unique oils, tailor-made to sublimate the finest cuisine. These partnerships have enabled the company to push back the boundaries of craftsmanship, combining culinary creativity with absolute respect for raw materials: one fruit, one oil.

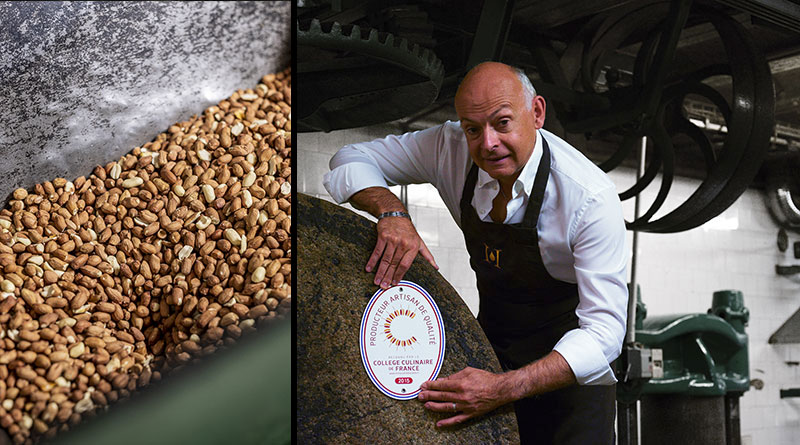

With a meticulousness worthy of the greatest masters, he perfects every stage in the manufacture of his oils: a rigorous selection of fruit, careful pressing, and an unrivalled passion for quality. For Jean-Marc, an oil is much more than a product: it's a promise of authentic taste and transparency, without artifice or compromise.

Today, his creations don't just seduce the world's Michelin-starred tables: they tell a story. The story of a visionary craftsman who, thanks to his know-how and prestigious collaborations, has chosen to sublimate the richness of fruit to offer a product of incomparable sincerity and excellence.